Apollo missions’ astronauts collected moon dust decades ago.

Today, researchers at UT San Antonio and the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) are analyzing those grains of dust to pave the way for the next wave of lunar exploration.

A new study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets details how space weathering alters the way lunar soil reflects ultraviolet light.

The research was led by Caleb Gimar, PhD, who recently completed a doctoral degree in the joint program offered by UT San Antonio and SwRI, with funding from the NASA Lunar Data Analysis Program (LDAP).

“By analyzing just a few grains of returned samples from the Apollo missions, we gain important insights into how the lunar surface has evolved over billions of years through “space weathering” — the relentless battering from solar wind and micrometeorite bombardment,” Gimar said. “This investigation reminds us of the immense scientific value of sample-returning missions, especially as we gear up to return to the moon with Artemis.”

Seeing the moon in a grain of lunar dust

To search for water on the moon, NASA relies on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been mapping the lunar surface since 2009.

The orbiter carries an instrument developed by SwRI called the Lyman-Alpha Mapping Project (LAMP). LAMP “sees” in the far-ultraviolet, allowing it to peer into permanently shadowed craters at the lunar poles — regions only faintly illuminated by ultraviolet starlight.

To reliably identify water ice in these polar craters, scientists first need to understand how dry lunar soil reflects far-ultraviolet light (accounting for differences in mineralogy at polar regions) so that they can separate water ice signatures from the soil itself.

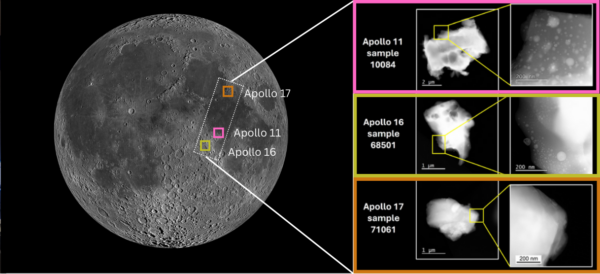

The research team analyzed soil samples from Apollo missions 11, 16 and 17. They discovered that the degree of space weathering is a primary determinant of the far-ultraviolet reflectance of the lunar soils, outweighing the influence of composition or mineralogy.

“A truly distinctive feature of this work is its connection across scales,” said Ujjwal Raut, PhD, a planetary scientist at SwRI, principal investigator of the LDAP grant and Gimar’s thesis advisor.

The team links nanoscale features revealed by electron microscopy with reflectance spectra measured at SwRI’s Center for Laboratory Astrophysics and Space Science Experiments (CLASSE) labs and uses those insights to interpret the moon’s ultraviolet images captured by LAMP from orbit, Raut explained. “It really is seeing the moon in a grain of lunar sand.”

To identify these nanoscale features, the team utilized the cutting-edge capabilities of the Kleberg Advanced Microscopy Center (KAMC) at UT San Antonio.

KAMC Director Ana Stevanovic, PhD, led the nanoscale imaging and compositional analysis of the Apollo-era grains. Using a state-of-the-art aberration-corrected transmission electron microscope, the team examined lunar grains at nanoscale to reveal thin space-weathered rims forged by eons of solar wind and micrometeorite impacts.

Implications for Artemis

“We used a powerful transmission electron microscope — one that can actually image individual atoms,” Stevanovic said. “What makes it unique is that it lets us not only see objects that small but also analyze their composition at the same time, all within a single lunar grain.”

The images revealed that heavily weathered grains are studded with countless tiny particles of iron, known as nanophase iron, the width roughly one ten-thousandth that of a human hair. Less weathered grains contained far fewer of these particles.

The study found that these tiny iron particles, along with microscopic pits, cause weathered soil to act like a rough, dark surface that scatters ultraviolet light back toward the source.

In contrast, less weathered soil, like the sample from Apollo 17, scooped from just a few centimeters beneath the surface, is brighter and scatters light forward, acting more like a mirror.

Understanding this distinction is vital for the Artemis program. As astronauts explore the lunar south pole, they will encounter a complex mix of heavily weathered terrain, fresher material churned up by impacts and polar regolith (lunar soil) of varying maturity — some potentially laced with water ice.

By combining electron microscopy analysis with lab reflectance measurements of Apollo-era soils, scientists can now robustly interpret LAMP data — distinguishing heavily space-weathered regions from newly exposed streaks of material created by crater impacts, and more importantly, dry soils from areas that may contain traces of water ice. The project highlights the strength of the collaborative research model between UT San Antonio and SwRI.

“By peering deep into Apollo grains with electron microscopy, we have unlocked a time capsule of the moon’s history, revealing how eons of space weathering influence the far-ultraviolet response of the lunar surface,” Stevanovic added. “It also highlights what collaboration between SwRI and UT San Antonio can achieve, demonstrating the strength of our joint scientific efforts.”